The decision

After setting out a useful summary of the key principles underpinning both grounds pleaded, the judge analysed the parties’ evidence. Noting that there were significant sales of football boots and other performance footwear under the double diamond logo and its widespread promotion, the judge held that the Umbro brand is famous in the UK in relation to sportwear and is particularly well known in relation to football kit and boots. This was so much so that the Iconix marks developed a high level of distinctiveness through use. Umbro was considered to have a substantial reputation for football boots and kit, with a lesser reputation for other performance wear.

Furthermore, the judge highlighted that Iconix did not challenge Dream Pairs’ evidence surrounding the creation of the contested logo which was purportedly designed by the founder without knowledge of the Umbro logo and brand. Additionally, there was no evidence of consumers making a link between the contested logo and the Umbro double diamond, not even by way of an Amazon review. Evidence of the results from a Google search of “dream pairs umbro” as put forward by Iconix was also criticised – the judge noting, for instance, that there were examples on reselling sites that failed to show either party’s logos and some of the evidence was seemingly from the US. This was unhelpful since it was not representative of the average UK consumer and related people (such as the person listing Dream Pairs on reseller sites and a YouTuber as noted below) were not called or approached for evidence.

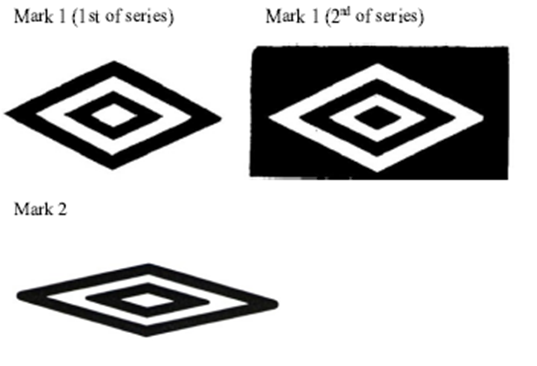

While the judge found identity between the contested logo being used on footwear with Iconix’s protection of footwear under Mark 2, there was a high measure of similarity in respect to the clothing goods solely protected by Mark 1. When considering the goods, the average consumer would exercise a moderate degree of attention. As to the similarity of marks – it was “very low indeed”. The court took the view that whilst the consumer may not notice the break in the outer figure of the contested logo on some presentations, the average consumer would notice the distinctive and dominant “P-like form” in the middle of the Dream Pairs logo.

Looking at the use of the contested sign in context, the judge commented that the high level of distinctiveness of the marks and the “substantial fame of the Umbro brand in connection with its use” would enable the consumer aware of the marks to associate the double diamond logo with the Umbro name. Furthermore, since the average consumer would notice the Dream Pairs Amazon page said nothing about Umbro, the goods being branded as something other than that of the marks (i.e. the Amazon page referenced Dream Pairs) was relevant when considering if the average consumer would likely be confused.